Yapping

\(2025\) is over! That was a once in a lifetime year. It was a perfect square, and the next one will come in \(2116\). Yet even that is not very cool number, because who cares about the square of \(46\)? \(45\) is a much nicer number than that. \(45\) is a triangular number (sum of the first nine positive integers in this case), so \(2025\) is the square of this triangular number, which you may recall also means it’s the sum of the first nine cubes.

\[ \sum_{i=1}^{n} i^3 = \frac{n^2 (n-1)^2}{4} = \left[\frac{n(n-1)}{2}\right]^2 = \left(\sum_{i=1}^{n} i\right)^2. \]

Also, since \(2025\) is the square of \(45\), it’s the sum of the first \(45\) odd numbers.

\(2026\), on the other hand, is unbelievably boring. Its prime factorization is literally just \(2\cdot 1013\). So, for the first CPOTM of the year, I’ll try to make \(2026\) more interesting by writing a disproof instead of a proof.

If you’ve seen it, then sorry. If not, here it is:

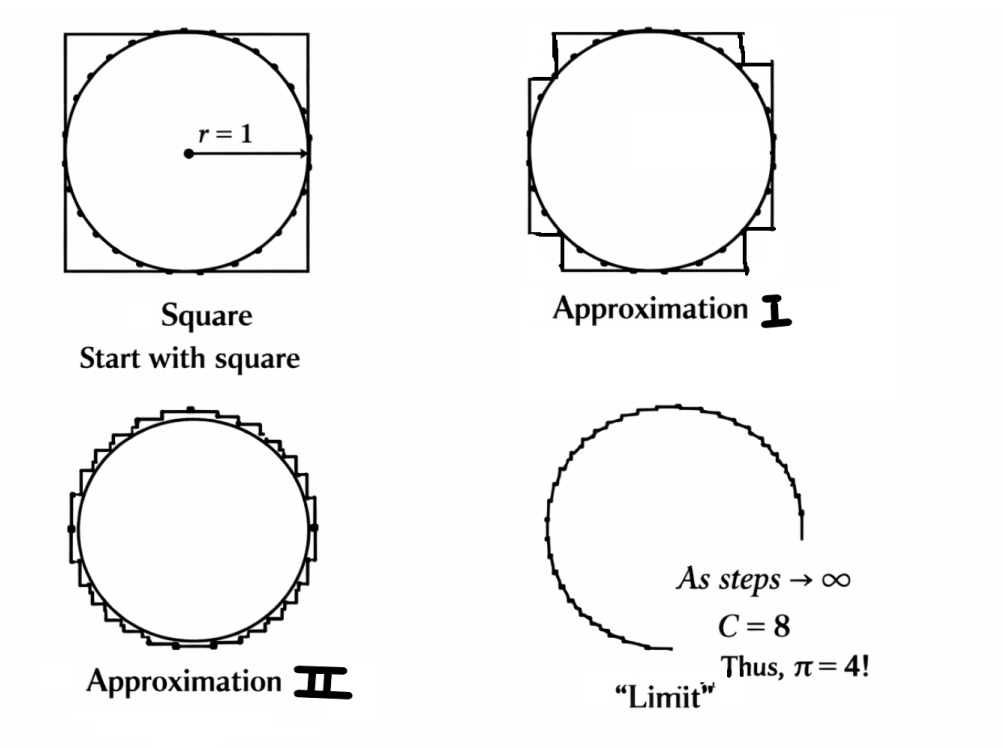

If you take a square of side length \(r\) and then keep on cutting the corners so you preserve the perimeter \(8r\), but the shape approaches a circle, then why can’t you say that \(\pi = 4\), because the diameter is \(2r\)?

Solution

It seems correct, doesn’t it? The area certainly converges, because after cutting off the corners over and over again, you get the same infinitesimal rectangles that could integrate just like a normal circle to get the same result.

The problem is that the perimeter doesn’t converge. The arc length of a curve from \(t=a\) to \(t=b\) where \(x\) and \(y\) are both functions of \(t\) is given by \[ \int_a^b \sqrt{(\frac{dx}{dt})^2+(\frac{dy}{dt})^2} dt \]

This is NOT the same as \(x(b)-x(a)+y(b)-y(a)\).

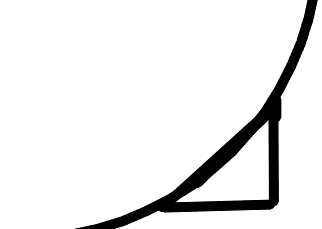

Are you still not convinced that the perimeter doesn’t converge? Zoom in on an infinitesimal piece of the diagram, which is where the arc length of the circle is basically a line.

In an infinitesimal piece, the limiting process just turns the square into a staircase-like shape, say of \(x\)-length \(dx\) and \(y\)-length \(dy\). On a tiny “step”, the perimeter is just \(dx+dy\). However, that tiny part of the circle is just a line that goes through the endpoints of the step, so the perimeter is \(\sqrt{dx^2+dy^2}\).

You might argue that maybe we should zoom in even more, and the snapshot we took wasn’t the true final result. However, the arc of the circle is already basically a line. By cornering in the square even more, you’re just going to get another line going through a step, and the situation won’t change, so we have, in fact, zoomed in enough. To actually make the square match the circle in its perimeter, we must directly make the horizontal and vertical lines turn into diagonal lines, which changes the perimeter. \(\blacksquare\)